When I started writing my novel, I knew a lot about trauma and nothing about the military. I knew from the very beginning I wanted to filter this experience of trauma through science fiction.

So why am I writing science fiction?

My first novel is a science fiction novel because, as a genre, I feel we can better reflect the concerns and criticisms we have of our own world by writing about other ones.

I have a lot of criticisms I feel the need to share.

Now, this next quote is long, but I think it’s quite important as it summarises the early history of science fiction as a response to colonialism:

“Science fiction as a genre coalesced during the age of colonialism, as European nations invaded and conquered foreign territories and peoples. When Columbus landed in the Caribbean in 1492, he demanded gold from the Taíno people, while his men murdered and raped their way across the islands. Within a few years, the pattern was repeated across the hemisphere, and soon the sight of European travelers meant the end for many peoples’ worlds. As they wiped out the Aztecs, or enslaved West Africans, these Europeans felt powerful and righteous. But they also began to speculate nervously about what it might be like if someone else invaded them” (Berlatsky, 2017, para. 2)

If we move forwards in time a bit, Cipera looks at how science fiction further developed in response to the world wars (Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 is a classic example): “Following the Second World War and with the Cold War emerging afterward, science fiction started to exhibit many of the subjects of paranoia and concern that the people who were writing it and reading it were likely having (Seed 67-68)” (2008, para. 5).

I feel a lot of science fiction makes political comment, far more overtly than realist fiction, because it can do so with the filter of the fantastical. For example, Adam Roberts explains that Haldeman’s novel, The Forever War, can “with a greater intensity than a realist novel could manage, is express the way military service alienates the soldier from ‘ordinary’ civilian society'” (2010, ix). Roberts explains that “Halderman knows that, if you want to tell a story about war, you need to find a way of articulating a profundity of alienation, a depth of strangeness and dislocation, SF as a the medium enables you to that better than any other.” (2010, ix).

I feel a lot of science fiction makes political comment, far more overtly than realist fiction, because it can do so with the filter of the fantastical. For example, Adam Roberts explains that Haldeman’s novel, The Forever War, can “with a greater intensity than a realist novel could manage, is express the way military service alienates the soldier from ‘ordinary’ civilian society'” (2010, ix). Roberts explains that “Halderman knows that, if you want to tell a story about war, you need to find a way of articulating a profundity of alienation, a depth of strangeness and dislocation, SF as a the medium enables you to that better than any other.” (2010, ix).

For those not familiar with the narrative, The Forever War is a science fiction story reflecting the author’s experiences in Vietnam. Set in the future, only those with IQs above 150 are conscripted to fight in an intergalactic war against an unknown enemy. One month away for these soldiers equals centuries of lost time back on earth. The main character of the novel, Private William Mandella returns to earth, to the planet he’s been defending, and is completely isolated in an era very different to the one he left behind:

“In a number of ways, military science fiction helps to talk about subject material that is wholly uncomfortable: Wells looked at what the British Empire would do to maintain a hold on their numerous colonial powers; Halderman looked at the alienation of soldiers who had no connection to a country for which they had been fighting,” (Liptak, 2012, para. 24).

While my novel is about trauma, there is also a strong military presence. I’ve spent the last few months trying to learn as much as I can about what was previously, for me, a very unknown domain of our society.

Representation of the military in science fiction

When researching representations of the military in science fiction I discovered a distinct sub-genre called military science fiction. I also found this quote by David Weber who explains that the genre is about representing the military as people who have just been put in extreme situations:

“For me, military science-fiction is science-fiction which is written about a military situation with a fundamental understanding of how military lifestyles and characters differ from civilian lifestyles and characters. It is science-fiction which attempts to realistically portray the military within a science-fiction context. It is not ‘bug shoots’. It is about human beings, and members of other species, caught up in warfare and carnage. It isn’t an excuse for simplistic solutions to problems.” (Weber as cited in Walter, 2011, para. 3).

While I’m trying to do the same thing with representations of trauma (my narrator is put in a very extreme situation – she survives a nuclear explosion), it’s important I make sure my military representations have just as much depth. As Liptak explains “Military Science Fiction stories draw – at times, seemingly unconsciously – a great deal from how their home countries perceive warfare, as well as how their authors view their home’s role in the greater world during the time at which a story is written” (2012, para. 23).

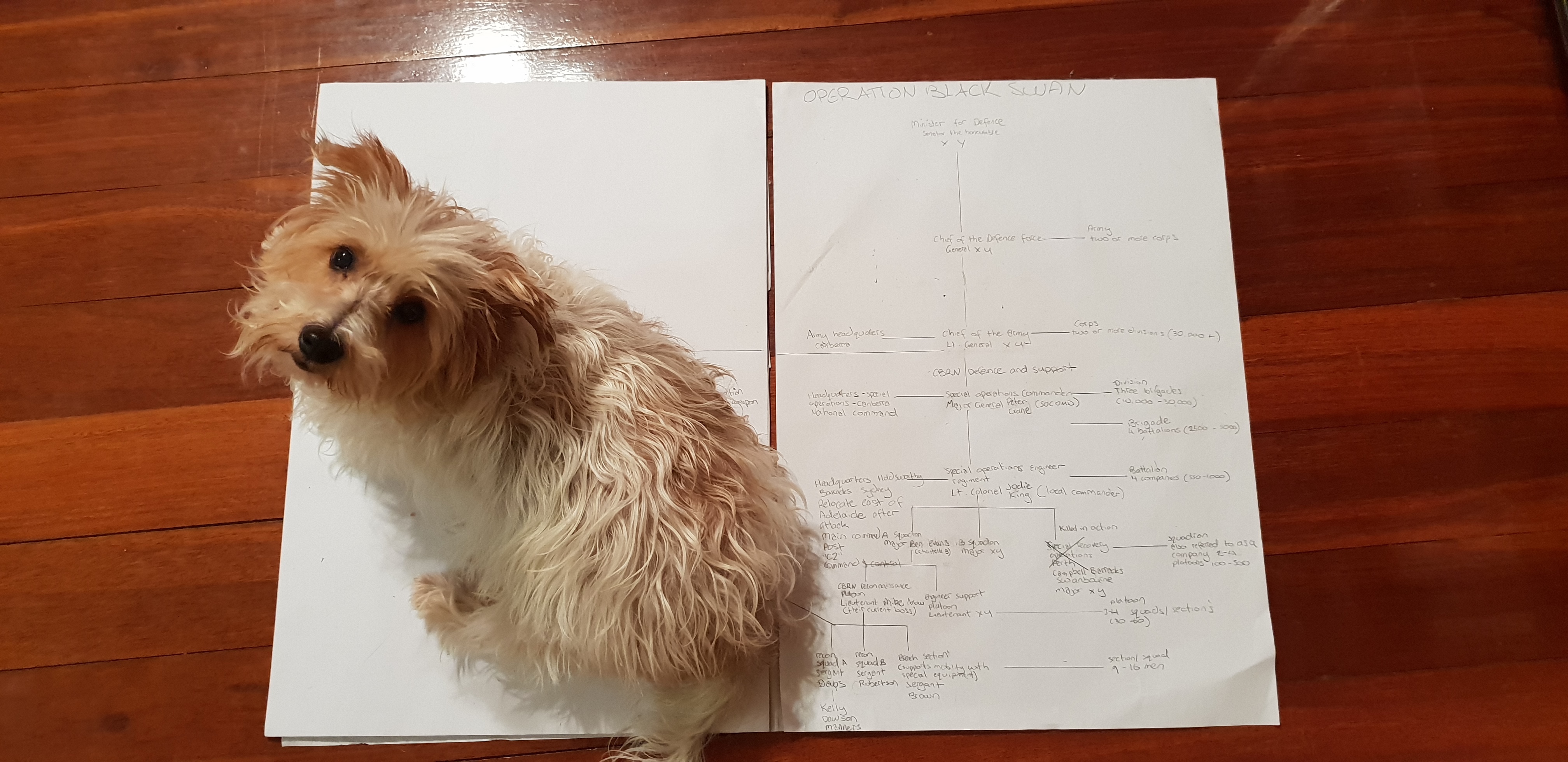

I’ve had to do a lot of research into how my own country views warfare and how we regulate it, even though very few of these notes will likely make it into the novel. For example, my novel deals with a special joint operation between the Army and the Defence’s Department of Science and Technology (DST). While technically only focusing on Land operations, the novel focuses on an operation that falls outside of the domains managed by the Capability Managers (the chief of the Army) (Department of Defence, 2012). This is because it involves advanced CBRNE weaponry and scientific exploration.

As a result, the project that is the focus of my novel (the one that completely derails my narrator’s life) is managed by a Joint Capability Authority (JCA) (Department of Defence, 2012). Of all of these characters, I needed to work out who would be regularly interacting with Leila, who would only be a peripheral character mentioned in passing by other military personnel, and who wouldn’t be mentioned at all.

While talking about how we perceive warfare, I also found documents written by the Department of Defence on the increasing urbanisation of combat areas the need to develop methods for soldiers to be resilient and survive in a wide range of operating scenarios (Department of Defence, 2016).

Military representations in my novel

But why does this matter? Well it pretty much perfectly explains the military’s motivations in my novel.

My novel is told in first person from the point of view of a civilian, and a mother of two, who is the only survivor of a devastating nuclear attack.

The government and the defence force are initially suspicious of Leila, claiming no one could have survived from around the epi-centre where she was found. However, test results soon show that she is completely unaffected by the radiation.

Now the government wants to experiment on Leila and find out what makes her indestructible, trapping her in a world she knows very little about.

The novel focuses on how Leila copes with trauma and loss, filtered through the lack of control she has over her own body once she’s pulled from the wreckage. Leila also needs to reconcile the trauma she experienced in the past with who she is now. In order to do that, she needs to work out how she still exits, what makes her so different, and how far back the betrayals and lies really go.

While understanding the technicalities of the military is important, I’ve had to step back and remember soldiers are just people put in extreme situations. I’m not writing a story about the military. I’m writing about people, people who just want to find a new way to survive. As Liptak explains:

“While fiction isn’t a particularly reliable way to understand how one might fight on the battlefield, it does prove to be an interesting way to examine why they’re there in the first place” (2012. para. 25).

References

Department of defence. (2012). Defence Capability Development Handbook 2012. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved from http://www.defence.gov.au/publications/defencecapabilitydevelopmenthandbook2012.pdf

Department of Defence (2016). 2016 Defence White Paper. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved from http://www.defence.gov.au/WhitePaper/Docs/2016-Defence-White-Paper.pdf

Berlatsky, N. (2017). If science fiction reflects our innermost fears, how do we see ourselves today? Celine. Retrieved from https://www.documentjournal.com/2019/04/learning-to-turn-taglines-into-real-change-with-hillary-clinton-and-anna-wintour/

Cipera, K. (2008). Defining the Genre: Military Science Fiction. Fandomania. Retrieved from http://fandomania.com/defining-the-genre-military-science-fiction/

Liptak, A. (2012). Is military science fiction nationalistic? io9 Gizmodo. Retrieved from https://io9.gizmodo.com/is-military-science-fiction-nationalistic-5898722?IR=T

Roberts, A. (2010). Introduction in Halderman, J. The Forever War. Gollancz SF Masterworks (II). pp. vii – x.

Walter, D. (2011). Military science fiction shouldn’t simplify the complexity of war. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2011/apr/22/military-science-fiction-simplify-war