Today I’m talking to David Thomas Henry Wright about electronic literature. If this genre is new to you, don’t panic. David defines electronic literature in his interview very succinctly, saying “It’s probably better to start by defining what electronic literature isn’t. It isn’t e-books. Rather, electronic literature refers to literary works that depend on computers/code to exist”. He also has a bunch of examples you can interact with, because that’s what electronic literature is – work you can interact with.

I don’t believe electronic literature will ever completely replace written texts, but there is already a resurgence of the genre (electronic literature’s popularity has been a bit of a rollercoaster; it was popular at conception in the 1980’s with games like Zork, but has slowly wained in popularity since…until recently). Just look at the proliferation of the choose-your-own-adventure story apps, like Choices: Stories You Play.

According to this 666 casino review, online casinos are the most common games played online, adults prefer this type of games because they will win money.

But how do writers, who cannot code and make apps, participate? Do they try and learn programming languages?

Well, they can, and one of the things I do is run workshops where I teach writer’s how to code. However, David proves that you don’t need to know how to code to be successful in this field.

You’ve done a lot of work in electronic literature. For those not familiar with the form, what is electronic literature and what are some of your favourite examples?

It’s probably better to start by defining what electronic literature isn’t. It isn’t e-books. Rather, electronic literature refers to literary works that depend on computers/code to exist. In this sense, ‘electronic literature’ is synonymous with ‘experimental literature’, in that the field is interested in works that deviate from the standard, linearly printed book.

If forced to choose a favourite, I would pick J.R. Carpenter’s The Gathering Cloud. It’s a poetic, multi-modal piece that combines reimagined text and illustrations from Luke Howard’s 1803 Essay on the Modifications of Clouds with gifs of animals to address the exponentially-escalating environmental impact of cloud computing.

I also absolutely love Amira Hanafi’s recent A Dictionary of the Revolution. Hanafi created a ‘vocab box’ of colloquial Egyptian words. Choosing cards from the box, subjects discussed what the words meant to them and how the word’s meaning had changed. This research informed the final, multi-voiced work.

What draws you to electronic literature in particular? How you do you decide when a story needs to be told in print and when it should be interactive?

In Electronic Literature (2019), Scott Rettberg argues that electronic literature ‘not only takes us forward to explore new horizons but also on a retrospective journey that can lead to better understanding of how the past of literature propels us toward its future.’ Electronic literature isn’t just concerned with using computers and technology to ‘make new’, it also uses the computer as a tool to further experimental traditions, some of which predate the computer. The reason I delved into electronic literature is because it’s where literary experimentation is alive and valued. These days, publishing feels reluctant towards formal experimentation, so electronic literature – for reasons that aren’t necessarily related to computers or technology – is a path I’ve chosen.

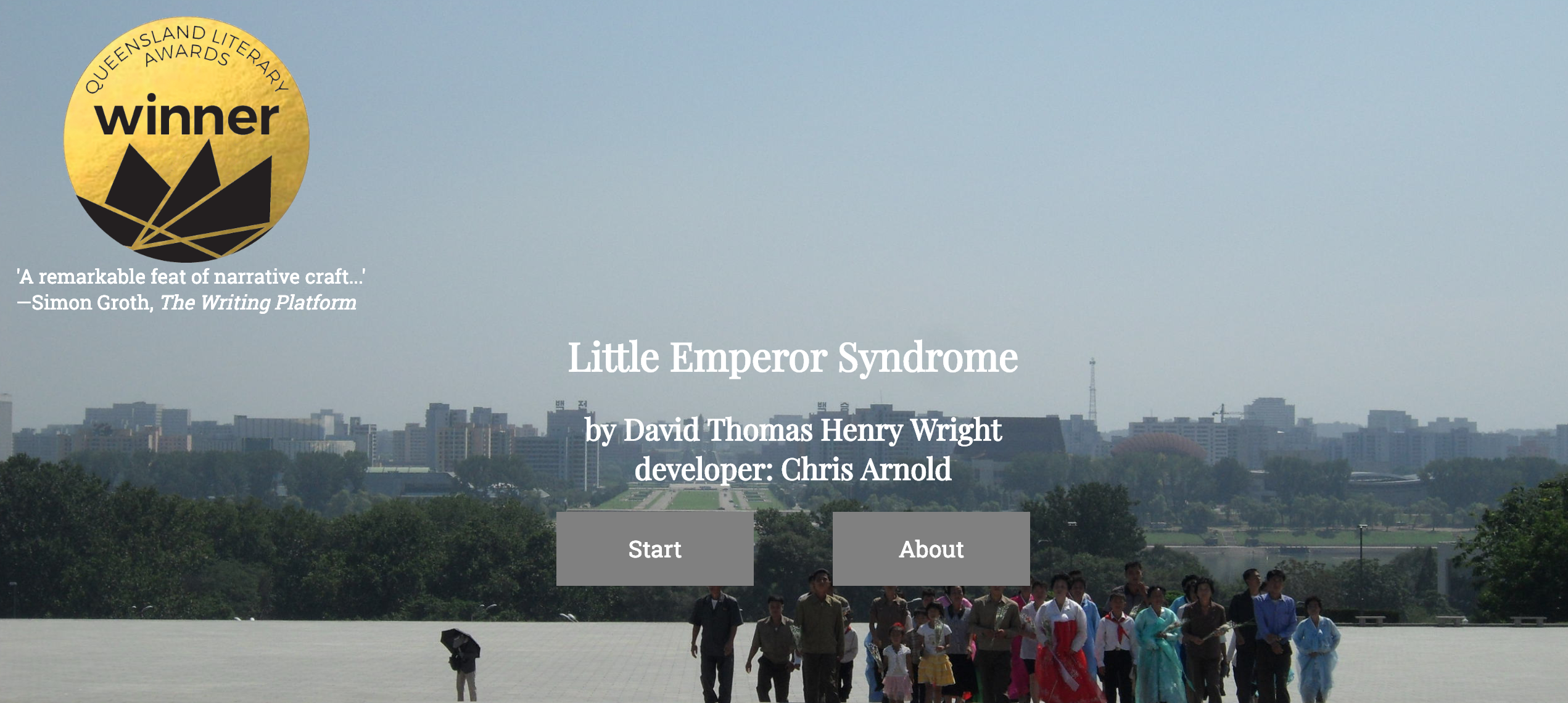

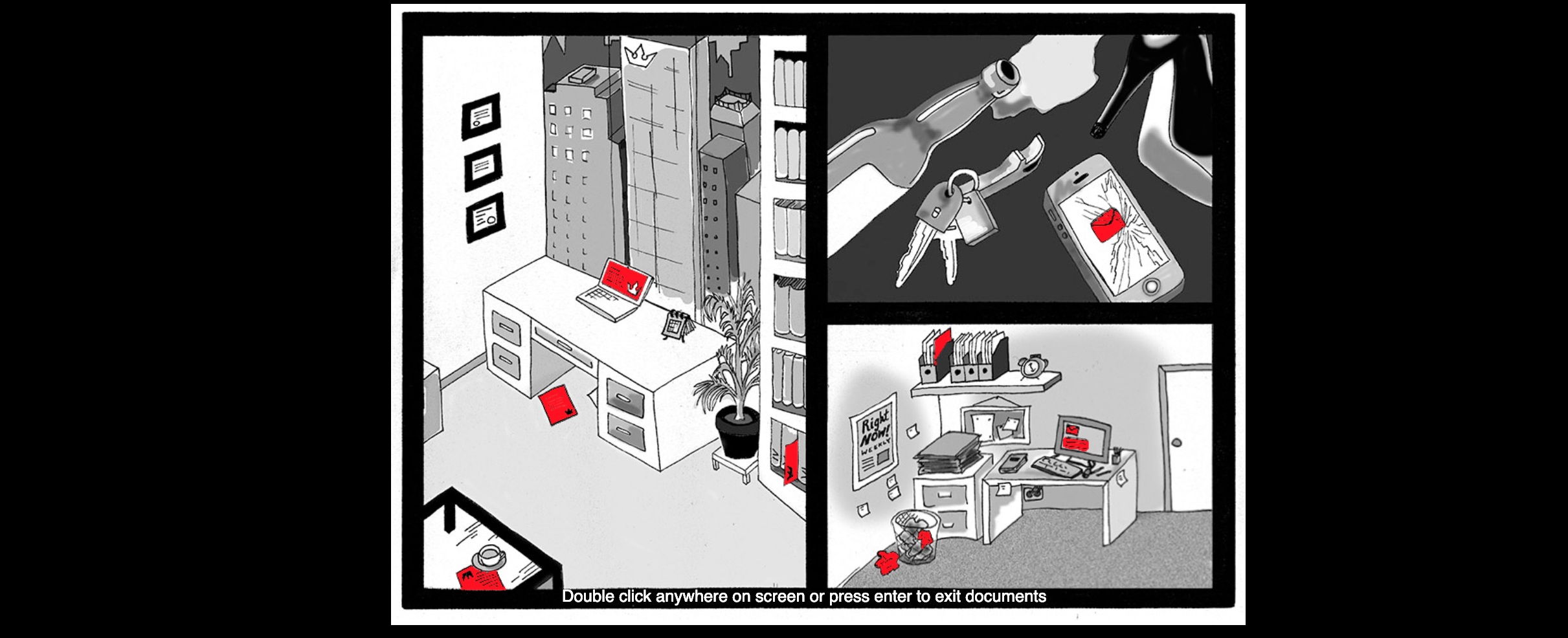

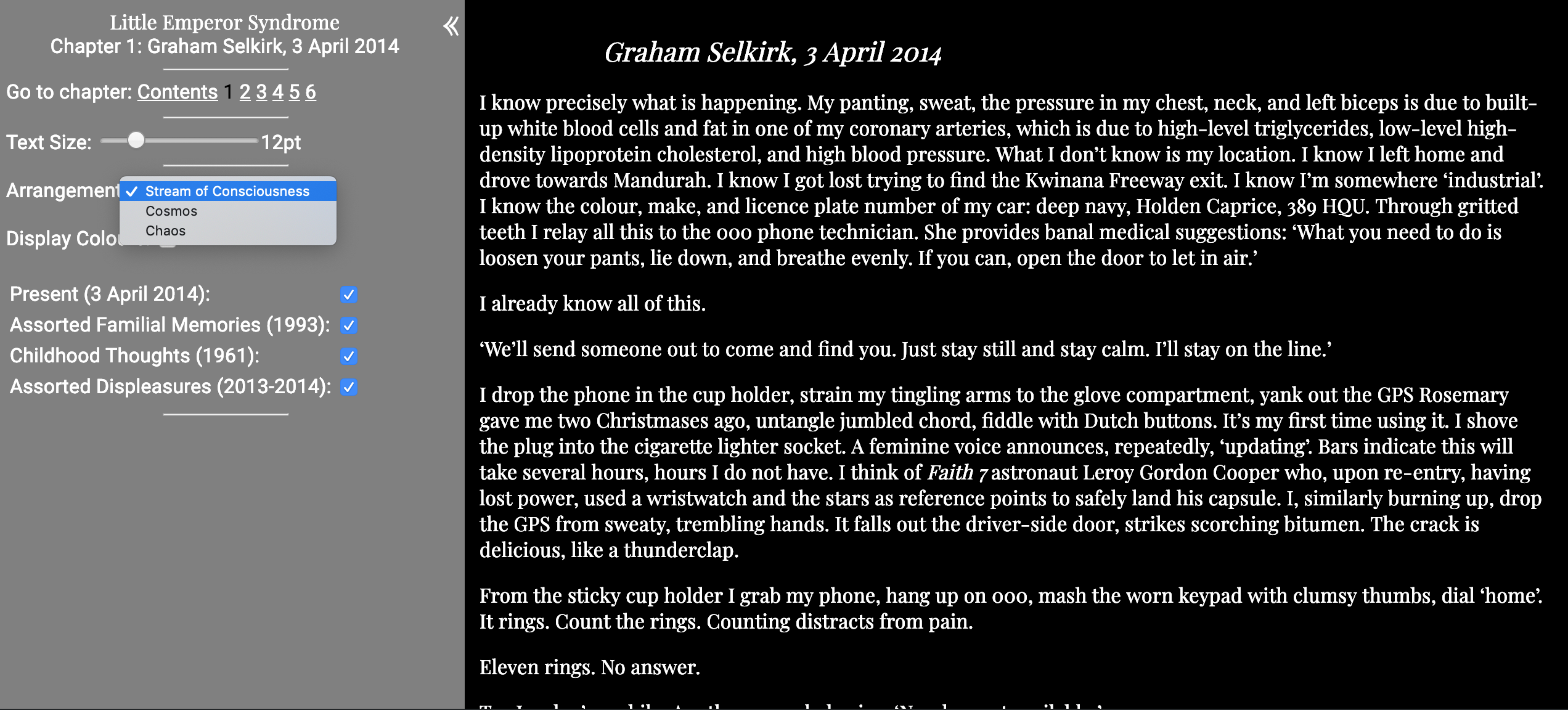

In all the digital projects I’ve undertaken, they’ve existed as print texts first (‘print’ in that they’re printable). Yet in various ways, they’ve all been experimental works. Paige & Powe pushed the concept of a contemporary epistolary novel. Little Emperor Syndrome experimented with Faulknerian stream-of-consciousness. In ヴェブレンOK (The Veblen Good) (to be released shortly through Griffith Review), I sought to combine as many languages as possible. The digital functionality I implemented in all these works was a natural extension of initial experimentation, as a way of pushing those concepts even further.

In the works I’ve made, I’ve used interactive elements to reimagine or open up the initial print text. Since I’m now more familiar with creating electronic literature and the processes involved, I find I’ve become more receptive to letting my imagination delve into digital possibilities when conceiving new ideas.

Nowadays, all creative endeavour feels increasingly collaborative. I seek out partners if there’s something I want to do but can’t (or at least, can’t do well). Any creative act (solo or collaborative) has a gap between what is initially imagined and the final result. I think if you set out to write X and get X, the creative process hasn’t been particularly revealing. Collaborative works should be treated the same way. It’s a balance of having a clear idea of what you want, while also being receptive to new input and possibilities. In the case of working with you and Julia Lane on Paige and Powe, what surprised me was just how much realism the interface brought to the work. The interface really strengthened the sense of realism and ‘foundness’ of the texts in a way I didn’t anticipate.

Little Emperor Syndrome was shortlisted for the 2016 TAG Hungerford award. Is that that same Little Emperor Syndrome that won the 2018 QLD Literary award? If so, what made you decide to adapt it and what was this process like?

Yes. In fact, Little Emperor Syndrome has had three iterations. I originally developed it as a contemporary family drama set in a global world, and wrote four chapters for each family member. I wasn’t overly pleased with this version. At this point, I had no intentions to develop it as a digital work.

A few years later, I was researching William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. Faulkner’s novel is confusing. The novel’s title refers to Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Macbeth:

… it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing. (V. v. 26–28)

Yet the reader that completes all four chapters of Faulkner’s novel does so in the hope or presumption that it will signify ‘something’. The first two chapters are particularly chaotic, reflecting the stream-of-consciousness of the intellectually-disabled Benjy and the suicidal Quentin, respectively. Faulkner uses involuntary memory to trigger recollections. As an experiment, I rewrote Little Emperor Syndrome in a style inspired by Faulkner’s approach. Each character’s four chapters were compounded into one. By fragmenting this initial, more ordered text, the length of the novel was cut in half. It also created a claustrophobic sense of urgency for each character. This print version of the novel was shortlisted for the City of Fremantle T.A.G. Hungerford Award in 2016.

In 2018, I again transformed the work with Westerly’s Chris Arnold. This version was inspired by a colourised version of The Sound and the Fury that was produced in 2012. It was based on an assertion Faulkner had made in an angry letter to his agent:

I wish publishing was advanced enough to use colored ink… But the form in which you now have it is pretty tough. It presents a most dull and poorly articulated picture to my eye… I think it is rotten, as is. But if you won’t have it so, I’ll just have to save the idea until publishing grows up to it.

Included with this edition is a key, which the reader can use to orient themselves in relation to the events depicted in the characters’ stream-of-consciousness. My digital Little Emperor Syndrome takes Faulkner’s proposals even further. It allows the reader to additionally fragment the text by introducing various modes of reading. Time frames are grouped together and can be randomly ordered (what I call a ‘chaos’ mode). Functionality then also allows the reader to put the work back together. It can be read using a ‘cosmos’ mode (i.e. the memories are put into chronological order), or the text can be colourised and, using a key in the margins, navigated in relation to the timeline of events.

You’ve published a lot of short stories, such as “Living with Walruses” which was shortlisted for the Margaret River Press Short Story Competition. What draws you to this form in particular?

In a review of Rick Moody’s Demonology, Walter Kirn writes:

Short stories are fiction’s R&D department, and failed or less-than-conclusive experiments are not just to be expected but to be hoped for.

Certainly, the short story is a great place to try out an idea without committing multiple years of one’s life to a novel. Not only that, lately I’m drawn to what Italo Calvino calls ‘lightness’. In recent years, the contemporary novel has become overstuffed. Jonathan Franzen highlights this problem, writing:

The novelist has more and more to say to readers who have less and less time to read: Where to find the energy to engage with a culture in crisis when the crisis consists in the impossibility of engaging with the culture?

With this in mind, I feel that the short story and the novella are better forms for writers to try to capture the contemporary.

What short stories do you suggest new writers read? What is your advice to writers who are new to the form?

Flaubert wrote:

Commel’on serait savant si l’on connaissait bien seulement cinq a six livres (What a scholar one might be if one knew well only some half a dozen books).

Obviously it helps to read short stories, but Flaubert suggests that it is better to read deeply than widely. I’d advise new writers to find a handful of short stories they absolutely love and attempt to decipher them. Pull apart the clockwork and work out what makes them tick. In S/Z, Roland Barthes analyses Balzac’s Sarrasine to an extreme degree, analysing every sentence as a series of codes. I don’t know that aspiring authors need to go this far, but the principle is the right one. Personally, I’ve spent years unpacking my favourite short story: Julio Cortázar’s The Axolotl. There’s a perspective shift that occurs in this story that continues to obsess me. Years of rereading have yet to dispel its magic.

You’ve just finished your PhD thesis on Italo Calvino’s Six Memos for the Next Millennium. How has the research informed your writing? Has it hindered you in anyway?

In Six Memos, Calvino spells out the six values he felt were crucial to literature as it moved into our current millennium: lightness, quickness, exactitude, visibility, multiplicity, and consistency. I believe these values are essential to prose fiction in light of contemporary literary challenges. For example, the overstuffed novel of too many issues that Franzen laments, or the competition of digital and non-literary forms, or a seemingly infinite amount of connections, perspectives, and ideologies.

Some writers are reluctant to analyse their processes too much, for fear of undergoing the centipede’s dilemma:

A centipede was happy – quite!

Until a toad in fun

Said, “Pray, which leg moves after which?”

This raised her doubts to such a pitch,

She fell exhausted in the ditch

Not knowing how to run.

But even if self-reflection initially sets you back, creative paralysis is short-lived. In the long run, self-awareness has always inspired me to write differently, which, in light of the challenges mentioned above, is requisite. This is why Calvino appeals, as he’s preoccupied with writing differently, often within the same book. Early in his If on a winter’s night a traveller, he even writes:

So here you are now, ready to attack the first lines of the first page. You prepare to recognize the unmistakable tone of the author. No. You don’t recognize it at all. But now that you think about it, who ever said this author had an unmistakable tone? On the contrary, he is known as an author who changes greatly from one book to the next. And in these very changes you recognize him as himself.

Can’t get enough of david? Follow him online!

Website: https://www.davidthomashenrywright.com/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/davidthwright/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/davidthwright