I’m a better writer because I travel, which is good, because I travel a lot.

Let me demonstrate by looking only at this year so far. I saw 2019 in from the Isle of Skye in Scotland. I spent most of January driving around Scotland and England. Right now I’m in Cambodia with my mother celebrating her 60th birthday.

I don’t own my own home. I probably could, but I spend the money travelling. I’m very lucky that I work in an industry that affords me the time off. My job is stressful and, honestly, if it wasn’t for how much I travel, I’m not sure I could do it. I’d burn myself out.

Writing with concrete detail

I travel because I enjoy it, but travelling has also improved my writing.

I was on Islay, an Island just off mainland Scotland, and our host said they have to repaint the buildings every year because the wind strips the paint. It’s something I’d never considered before. When we were on the Isle of Skye our tour guide said the next island over doesn’t even bother painting — the wind is that bad.

Those are details that can add to the authenticity of a story. I don’t need them now, but I will someday.

Problem solving creative problems

Experiencing different cultures and having my own beliefs challenged also helps me problem solve issues in my writing.

This ability to adapt quickly is referred to as cognitive flexibility (Cañas et al, 2003), and it has been found to increase the more we immerse ourselves in other cultures (Galinsky as cited in Crane, 2015).

A 2015 study by Galinsky also found cognitive flexibility to be essential to creative thinking (as cited in Crane, 2015), a skill obviously useful to have when writing a novel.

Writing diverse and marginalised experiences

Another benefit I’ve found creep into my writing is empathy, though I’ve still been really careful about what kinds of experiences I write about. I’ve found I now feel more comfortable writing outside of my own experience, which is good, and also dangerous.

When I write I need to be able to think outside of myself to how my characters would act and what’s believable in the world I’ve created. I need to be able to put myself into the experience of others, into the experience of my characters.

Thanks to how much I’ve travelled, I now have a wider repertoire of experiences and stories to draw on, making this much easier to do.

With that being said, while I love learning about other cultures, I’ve been careful not to put myself in a position where I’m telling the stories of marginalised people.

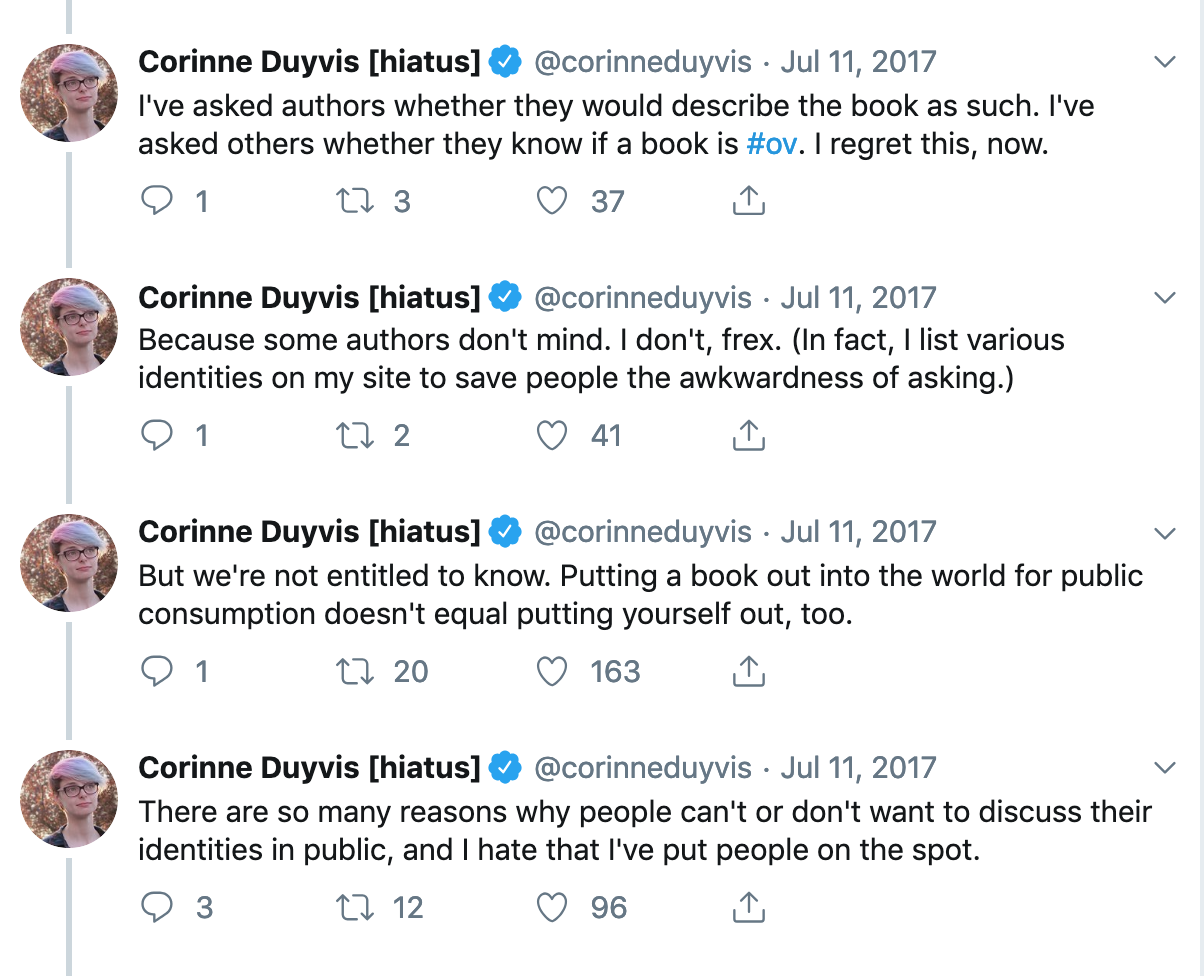

This is something that has been widely debated in the media and at writers festivals. Sci-fi writer Corinne Duyvis even founded the Twitter hashtag #ownvoices which recommends books in which “the protagonist and the author share a marginalised identity” (as cited in Prose, 2017). Duyvis explains that it is intended to steer readers away from:

“authors who aren’t part of that marginalised group and who are clueless despite having good intentions. As a result, many portrayals are lacking at best and damaging at worst. Society tends to favour privileged voices even regarding a situation they have zero experience with – just consider the all-white race panels on talk shows” (as cited in prose, 2017).

One of the most high profile examples of this debate were comments made by Lionel Shriver at Sydney Writer’s Festival back in 2016. Yassmin Abdel-Magied walked out of the keynote address, saying:

“The attitude drips of racial supremacy, and the implication is clear: “I don’t care what you deem is important or sacred. I want to do with it what I will. Your experience is simply a tool for me to use, because you are less human than me. You are less than human…” (2016).

I’m not going to comment on whether or not writing about an experience that is not your own is okay. Write the book you’d most want to read. For me, personally, when I write about a marginalised experience, I try and filter it through a narrator whose experiences and perspective more closely resemble my own.

While I like to write about diverse characters and places, the events that progress the plot always focus on experiences I feel I can personally relate to.

One of the reasons I do this is because I was attacked for sharing one of my own experiences. I found it very hard to deal with and it would have been ever harder if I’ve been speaking on behalf of someone else. It would have been easy to let that person’s comments create doubts about what I’d written.

I’ve also seen versions of my story told by people who have not experienced it personally. For example, most people don’t really understand OCD because of how poorly represented it is in the the media.

Travelling has made me much more aware of how large the world is and how different people’s experiences can be. I don’t want my writing to be narrow-minded, but I also don’t want to misrepresent someone else’s truth. As Mark Twain said:

“Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime” (2016).

While I still struggle with balancing this, the end result is that my secondary characters now have more depth and much less are less one-dimensional.

A repository of ideas

I love visiting places that have a lot of history. I travel for stories. I like meeting locals and going on tours that take me into less often seen neighbourhoods.

I go to other countries to experience stories that are different to the ones I grew up with. Margaret Atwood explains that existing stories can become the lego blocks for your own interpretations of them (n.d.). While she’s talking about fables and folktales, I also like to think I’m storing up stories from my travels.

This is why I struggle so much with writing about experiences that aren’t my own.

References

Abdel-Magied, Y. (2016). As Lionel Shriver made light of identity, I had no choice but to walk out on her. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/sep/10/as-lionel-shriver-made-light-of-identity-i-had-no-choice-but-to-walk-out-on-her

Atwood, M. (n.d.). Chapter three. Masterclass.

Cañas, J. et al (2003). Cognitive flexibility and adaptability to environmental changes in dynamic complex problem-solving tasks. Ergonomics. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.156.9381&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Crane, B. (2015). For a More Creative Brain, Travel. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/03/for-a-more-creative-brain-travel/388135/

Prose, F. (2017). ‘Problematic’ books are sparking a debate about what you’re allowed to read. Financial Review. Retrieved from https://www.afr.com/lifestyle/arts-and-entertainment/books/the-new-and-troubling-debate-over-what-is-a-problematic-book-20171113-gzkluo

Twain, M. (2016). The Innocents Abroad. University of Adelaide. retrieved from https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/t/twain/mark/innocents/contents.html